Willard’s Story

Stephen H. Willard: The Story of His Life and Work as a Master Photographer and Painter

“The conception of a picture is a spiritual thing”

“The conception of a picture is a spiritual thing”

By Richard J. Westman

for The Historic Willard Studio

at The Gallery at Twin Lakes

Mammoth Lakes, California

September 2014

Forward

Willard’s fascination with the wonders of nature began in his early years when his mother would take her children and their friends for hikes into the hills nearby where they lived in Corona, California. He began photographing those scenes when he was given his first camera by his father at age 14 and that led to a lifelong career. In his teens, he roamed the deserts and wandered deep into the mountains where, as a self studied photographer, his images garnered the attention of prominent naturalists who published his photographs in well known east coast journals as early as 1915 when he was only 21 years of age. Over time, his photographic efforts helped foster the designation of several wilderness areas as national parks.

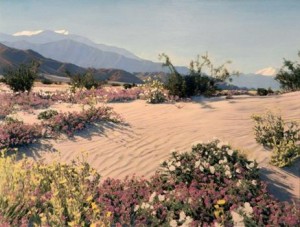

Willard was drawn to the subtle hues and contrasts that he referred to as the “land of the purple shadow” as he roamed the southwest deserts. He established a studio in Palm Springs in 1922. There his wife Beatrice sold his photographs and extolled his artistry as she did throughout their many years together, while Stephen shunned the spotlight preferring instead to pursue his passion to portray the unique offerings of nature that he found along the dusty trails and replicated so faithfully in his darkroom.

The Willards sought relief from the summer desert heat and established a second studio in Mammoth Lakes in 1924, a region of the Eastern Sierras that provided majestic landscape scenery in distinct contrast to his desert images for which he had gained his first notoriety. In 1947, the Willards left their home in Palm Springs, to operate only the studio in Mammoth Lakes where the wide open spaces of the Eastern Sierras suited Willard’s affinity for unspoiled solitude.

Willard became a master of his craft, albeit his having to rely on the primitive equipment and methods that were available, especially in his remote, “off the grid” mountain studio. Through patience and expertise gained without even so much as a light meter, he was able to capture just the right exposures which he transferred from contact negatives directly to riveting photographic prints which compare favorably to better known photographers of his era.

But that was not all. To provide even more entrancing images in color, Willard mastered the combined artistry of photography with painting in Rembrandt oils over enlarged photographs. The combination of these mediums adds texture and hues that illuminate the scenes portrayed with realism and beauty in an eye-pleasing manner that is unique to Willard’s work.

As a private man who was more interested in achieving excellence in his craft than the wide acclaim enjoyed by colleagues, who focused more intently on self promotion and business success, Willard’s work is only now gaining the prominence it rightfully deserves.

– Dick Westman

The Formative Years

Stephen Hallet Willard was born on March 8, 1894 in Earlville, Illinois to Stephen Sylvester and Elizabeth (Bettie) Park. Stephen’s father, Stephen Sylvester Willard was a dentist. In 1895, when Stephen H. was only one year old, the family , which included an older sister Madeline, moved to Corona, California where his father opened one of the first dental practices. Bettie taught the children at home for many years and loved to take them and their friends on hikes in the nearby hills. She loved history and collected Indian baskets. Bettie was an artist and painted this portrait of Stephen at age two, in curls and infant dress typical of the 1890’s:

The seminal event in Stephen’s life occurred when, at age 14, his father gave him his first camera. Stephen later said:

“…as a youth of fourteen years, my father led me to the summit of a pass in the Sierra Madre Mountains to look down for the first tie upon the desert. Little did I realize that day that the picturing of this great subject was to become my life’s work. But the impression had been made, and it was natural that I became as the hunter, who once having seen the shadow of a bird greater than all others, should no longer be satisfied with the ordinary game, but leave all to pursue the extraordinary. Already interested in landscape photography, I soon began to attempt to put into graphic form the things that I saw, or rather felt, about all natural landscapes.”

Bettie died the year Stephen graduated from high school in 1912. Stephen attended Pomona College for one year but, having acquired sufficient skills with his camera, he decided to pursue what became his life long career in photography.

Stephen’s Early Years in Photography

In the August 1912 issue of Photo Era Magazine Willard is listed with those awarded Honorable Mention for spring photographs for the Round Robin Guild monthly competition. He was just 18 years of age. Ironically, his name appears, as listed alphabetically, next to Edward H. Weston who later became a quite famous photographer and good friend of Ansel Adams.

Stephen established a small studio in Corona in 1913 featuring local photography and scenes from the southwest Colorado Desert.

In 1915, Willard, at age 21, wrote an article for The American Annual of Photography entitled “With the Camera on Desert Trails,” observing that:

“The desert seldom photographed and looked upon with horror by the average person offers opportunities, many and unique, to the pictorial worker in photography. The idea held by most people that every mile of the desert is like every other mile could not be a more mistaken one. Let one take his camera, canteen, blankets and provisions, and go out for a week’s stay in the desert solitudes, and he will always come back deeply impressed by its supreme majesty and mystery. The mystery of the desert fascinates one, once having been in the desert enough to really understand it, you will always want to get back to its solitudes”

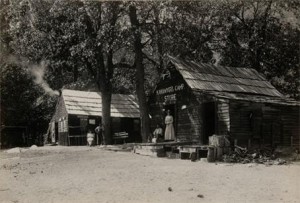

King’s Canyon

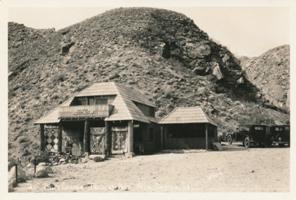

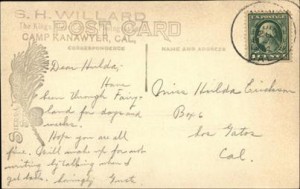

In the early years of his photographic career, from 1913-15, Willlard ventured into the Western Sierras in an area known today as Kings Canyon. He operated out of a tent studio at Camp Kanawyer near where Copper Creek flows into the south fork of the Kings River. Camp Kanawyer was a rustic resort that provided lodging, supplies and services to those hearty souls who made the long arduous trip into the back country.

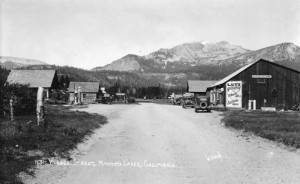

Photo of Camp Knawyer by S. H. Willard (courtesy E-Humanity.com)

Photo of Camp Knawyer by S. H. Willard (courtesy E-Humanity.com)

Willard captured scenes in the Kings Canyon area and sold postcards as “The Kings Canyon Photographer:”

Postcard by S H Willard, published by Sierra Forrest Studios at Camp Kanawyer, postmarked 1914

Postcard by S H Willard, published by Sierra Forrest Studios at Camp Kanawyer, postmarked 1914

It was at Camp Kanawyer that Willard, at about 20 years of age, likely met and was, perhaps, mentored by Charles Francis Saunders who went on to become a well known naturalist and author of a number of books providing information about the west and the Sierras. Saunders spent time in the Kings Canyon area and stayed at Camp Kanawyer around the same time that Willard was there. Willard’s relationship with Saunders is evident in later years in their association together in what has been described as the “Creative Brotherhood” by Professor Peter Wild. The Creative Brotherhood was a group of naturalists, authors, artists and photographers who lived near each other, traveled together throughout the Southwest, helped with each others’ works, and exchanged photographs which appeared in their various books.

In Saunder’s book, Finding the Worth While in California, published in 1916, he described the route Willard would have also taken back into Camp Kanawyer as a day and a half pack trip from the nearest road:

“Civilization is left behind, and the primeval forest swallows you up. Joe, the packer, on his wiry cow pony heads up the procession, leading his string of pack animals with jingling bells and tightly cinched burdens. The trail strikes at once into the Sequoia National Forest, through unspoiled woodlands of yellow and sugar pines, Douglas pruce and silver fir who feathery crowns mingle a hundred feet above you through which the sunlight sifts in tempered radiance. Now and then the twilight of the wood listens to clear day, and you cross a grassy meadow where wild flowers, in purple, scarlet, and yellow riot in the sun. All along is the joy of abundant water – cool springs gushing by the trail side, and brawling brooks tumbling to the unseen river.”

This was the entrancing wilderness that Willard encountered when he ventured into Kings Canyon in the High Sierras. Saunders set the scene of what Willard likely experienced when he arrived at Camp Kanawyer:

“Mother’ is there to greet you with a cheery ‘Howdy, boys,” and a hearty grip of the hand . . . It is literally carved out of the forest – its cabins, store and furniture being split out of the neighboring pines and cedars. It is primitive, but delightful from its very primitiveness, and you may either board and lodge her outright for a couple of dollars a day; or camp under the sky and board yourself out of the store with the addition of such meals in the dining room as you may elect to take. The kindly hostess of this camp (whom all the Sierra knows as “Mother”) is a born home maker, and adds such specifically feminine gifts as the ability to mend torn garments, make delectable doughnuts and elderberry jelly, and bind up the human anatomy, the more masculine accomplishments or riding, shooting, handling a park train and catching the limit of trout any morning in season before breakfast.”

|

|

Campsite Photos by Charles Francis Saunders (courtesy E-Humanity.com)

Saunders described a favorite trek of 40 miles round trip from Camp Kanawyer by Bubbs Creek to Bullfrog Lake and on to the Kearsarge Pinnacles where:

“lie multitudinous lakes of crystal clear water, reflecting with mirrorlike faithfulness sky and clouds and the peaks that hem them in. Bullfrog Lake is one of the loveliest of these.”

Willard traveled throughout this area as well, climbing over 11,000 ft. passes with his large format camera and tripod to capture stunning images of the spectacular back country wilderness.

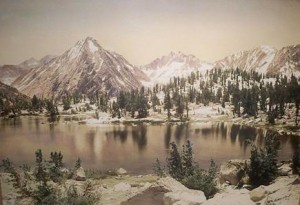

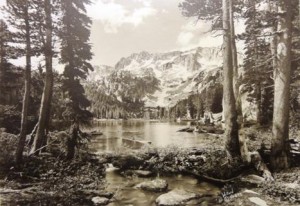

Bullfrog Lake

This early hand colored photograph by Willard is of Bullfrog Lake in Kings Canyon National Park (signed and dated 1916). A b/w print of this same scene is included in The Book of National Parks by Robert Sterling Yard, published in 1919 that promoted the creation of a Roosevelt National Park (later to become Kings Canyon National Park).

Willard’s photographic work in King’s Canyon gained national attention in an article by Charles Francis Saunders entitled “The Canyon of the Holy Kings” which appeared in the December 1915 issue of Travel magazine containing 11 scenic photos by Willard. The magazine was published by the passenger department of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad.

Since Willard was still a young man in his early twenties who was ensconced in west coast venues, one can arguably speculate that his work with Charles Francis Saunders led to his introduction to Robert Sterling Yard, the Educational Director of the National Park Service in Washington, D.C. Willard’s photos of scenes in Kings Canyon were used by Yard to promote designation of the area as a National Park in The New Country Life (1918), Ladies Home Journal (1918), The Book of National Parks (1919) and the National Parks Portfolio (1921) all venerated east coast publications.

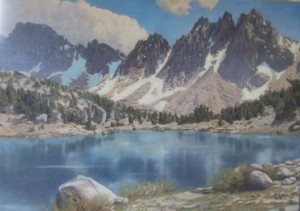

Later in his career, when Willard mastered the unique artistic skill of applying oils to enlarged photographs to create stunning paintings, he hearkened back to a scene he captured at the Kearsarge Pinnacles which was depicted in a Saunder’s article in Travel entitled “The Canyon of the Holy Kings.”

Saunders, in his article aptly captioned this image by Willard:

“In the evening light, when the Sierra’s jagged crests flush with alpenglow and, again, inthe virgin light of early morning, the lake reveals itself to you like a crystal gem set in the everlasting hills.”

Bear Valley Photographers

For a brief time, around 1916-17, Stephen partnered with Wright M. Pierce, whom he had known since his days at Pomona College, in what they called “The Bear Valley Photographers” producing and selling photos and postcards from the area surrounding Big Bear Lake. Pierce went on to become a noted ornithologist.

World War I

In 1918, Stephen enlisted in the army as a photographer and served in the 319th Engineer Battalion, 8th Division (A.E.F.) in France during WWI. He photographed the camp and soldiers as well as the landscape and people of France. Many of these images were printed as postcards and sold to the troops. He was discharged in the summer of 1919 and moved to the Palm Springs where he established a studio and a summer studio in Idyllwild.

Willard’s book The Desert of Palms

In 1919, Stephen wrote and published a booklet entitled The Desert of Palms in which he expressed his fascination with the desert. The text was interspersed with his desert photos and describes his journey through the desert and his observations of its unique beauty.

“Because we know that the desert breeze is in the palm trees, and out there in the open, the sun still shines on plain and mesaland, and all day long, in purple sleep the mountains lie. We know that the lilac hazes still cover the hills, filling the valleys and canyons, and the scent of sage still floats on the breeze. We know that the fire still burns at the mountains’ tops as the sun sinks to its home in the west, and the coyote, outlaw of the desert, still cries at nighttime. We know that the desert’s secret is never given up, and so its spell is never broken.”

Palm Springs

In 1921, Willard met Beatrice Armstrong in Idyllwild. They were married later in that year. After a year of traveling and photographing the deserts throughout the southwest, they settled in Palm Springs at a time when the population was only 200. In 1922 they built a home on Indian Avenue. Stephen exhibited his photos at The Desert Inn Gallery and Beatrice ran the trading post in Palm Canyon that also sold his photos.

Willard photo of Palm Canyon Trading Post

On December 19, 1925, their daughter, Beatrice Elizabeth Willard was born. She would be known as “Bettie.” She grew up in a family that inspired and nurtured her early interests in the beauty and wonders of nature. At an early age, she was encouraged to explore and read about the plants, animals and lakes where she lived. At age 12, she was guiding people around Mammoth Lakes and educating them about the terrain. By age 18, she had developed a sizable guiding business. She graduated from Stanford University with a degree in Biology in 1947 and completed a field study in Yosemite the following year. She moved to Boulder Colorado in 1957 where she attended Colorado University and earned an M.A. in 1960 and PhD. in 1963 in Botany.

Dr. Willard created the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering Ecology at the Colorado School of Mines. She served for five years as a presidential appointee during the Nixon and Ford administrations on the Council for Environmental Quality. She co-authored four books, among which was A Guide to the Mammoth Lakes Sierra (1959), edited by Genny Schumacher (Smith) which contained numerous photographs by her father as illustrations.

In 1929, Stephen and his wife built a beautiful Mediterranean style home on South Palm Canyon Drive which has become part of today’s Moorten Botanical Gardens.

Stephen established a studio at 116 South Palm Canyon Drive where he sold fine art photos and photo paintings and engaged in some commercial photography. He became a prolific publisher of postcards depicting scenes from the desert and advertising local resorts and hotels. His work in promoting the Palm Springs area through his photography later earned him recognition as one of the early pioneers in the development of Palm Springs.

The Measure of the Man

The measure of a man can, to a large extent, be judged by who he emulates and the company he keeps. Stephen Willard was a private man of whom little is known. But, perhaps, something can be learned from a study of the individuals that were his trusted associates and colleagues.

Among Willard’s personal effects after he died was a book by John C. Van Dyke, The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances, written in 1901, in which Willard had interspersed his own photographs of desert scenes. There is little doubt that Willard appreciated Van Dyke’s wisdom and views regarding the subtle beauty he found in the desert which is embodied in this quote from the book:

“I shall never be able to tell you the grandeur of these mountains, nor the glory of the color that wraps the burning sands at their feet. We shoot arrows at the sun in vain; yet we still shoot.”

Such a sentiment aptly describes Willard’s lifelong pursuit to capture the natural wonders he observed through his art.Stephen belonged to a “Creative Brotherhood,” as described by Peter Wild, in the Palm Springs area that included authors J. Smeaton Chase and Charles Francis Saunders; naturalist Edmund C Jaeger; cartoonist and painter Jimmy Swinnerton; author George Wharton James; Carl Eytel; and photographer Fred Clatworthy. The men lived near each other, traveled together throughout the Southwest, helped with each others’ works, and exchanged photographs which appeared in their variousbooks.

Willard was curious by nature which led to his exploration of faraway places. He and Beatrice traveled the world to remote places such as the Sahara and the Himalayas as well as many other locations in Europe, South America, and Asia. By 1942, it was reported that they had traveled 300,000 miles during their journeys, mostly by steamship often requiring trips onboard lasting as much as 3-4 weeks at a time. They used the Dollar Steamship Lines which featured a program of world travel where one could stop off in one location, spend whatever time was desired, then get on board another ship to the next destination.

Death Valley and Joshua Tree

During the 1930’s, Willard was hired by the U.S. Borax company to document their work in Borax mining in Death Valley. Some of his work helped popularize the “twenty mule team” and was used in advertising products for U.S. Borax. Willard’s photographs were used to promote the Death Valley area and resorts through his work with the Union Pacific Railroad and the Death Valley Hotel Company. In 1933, Willard’s Death Valley photographs played a key role in President Hoover’s decision to add land to the park.

|

|

In 1936, Willard’s photos were again used to support the proposal and decision to create

the Joshua Tree National Monument.

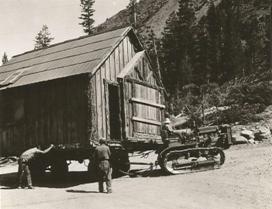

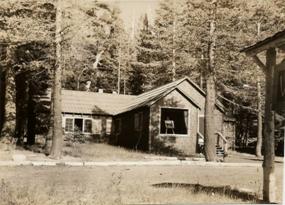

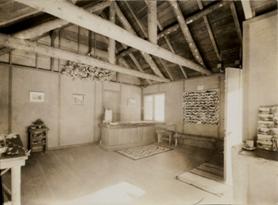

Mammoth Studio

In the quest to find a cooler mountain setting to spend their summers, Stephen and Beatrice established a studio and home in Mammoth Lakes in 1924. Beatrice said:

“We fell in love with Mammoth. . . we worked very hard and long hours to build a tiny studio and living quarters. We didn’t have much, but managed to get along by doing much of our own work, even photo finishing in those first years. Wanting something rustic in our studio in keeping with the rugged outdoors, we had pine slabs with the bark brought up from the sawmill.”

In 1934, they were given notice they would have to move up on the new highway being built to the lakes to what Beatrice described at a “perfect spot, a sheltered area in the pines well above the road where it was never windy.”

|

|

The studio was more than a business to the Willards, more like having a big family, as people and friends returned every years, if only to chat awhile. There aim, always, was to encourage visitors to see all the points of interest and to know the history and tradition that is Mammoth.

Stephen outside the studio in 1965,

Stephen outside the studio in 1965,

the year before he died (photo by Rick Warner)

Throughout their lives together, Beatrice was constantly there to support Stephen. While he lurked back in the darkroom, she would be out front in the studio extolling her huband’s work.

After Stephen’s death in 1966, Beatrice continued to operate the studio and to sell Stephen’s work until a year before her passing in 1977.

Recording the History of Old Mammoth

During Willard’s earliest days in Mammoth, remnants remained of the Old Town of Mammoth and the gold mine that fueled its brief surge in population when it reached its peak of around 500 in 1880. Willard’s photographs documented the relics left behind at the mine, at a time when some structures were still standing unmolested.

|

|

Willard also took photographs of Old Mammoth as it existed during the early days when he and Beatrice arrived.

Move to Lone Pine

In 1947, discouraged by increasing development where they had live in Palm Springs and Coachella Valley area, the Willard’s sold their home in Palm Springs and moved to the Owens Valley where they settled on their ranch in the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, in the shadow of Mt. Whitney. There they built a comfortable “off the grid” residence with a self sustaining water supply, a garden, and fruit orchard. Stephen and Beatrice lived out their lives there.

|

|

Photos by Rick Warner

Master of His Craft

Willard became a master of his craft, albeit his having to rely on the primitive equipment and methods that were available, especially in his remote, “off the grid” mountain studio. Through patience and expertise gained without even so much as a light meter, he was able to capture just the right exposures which he transferred from contact negatives directly to riveting photographic prints which compare favorably to better known photographers of his era.

His philosophy relating to his work can best be captured in his own words:

“I feel that the conception of a picture is a spiritual thing, that no landscape artist can possibly be successful unless he has definite feeling for the subject he is trying to interpret. Otherwise, no matter how perfect geometrically the composition may be, the final result will be as dead as a man without a soul.”

In describing his technique he said:

“To me a good composition should allow the eye to enter easily from one side of the center or the other, to travel naturally forward into the middle distance, preferably along a curving line. The eye should be allowed to reach the distance, which should usually be the strong point of the picture without too much interference. It will do so readily if the line and masses of the picture are strong enough, and properly arranged.”

“Many if not most of my best pictures have been made by continual hunting over and traveling back to areas which are particularly suited to carry out the ideas I was trying to express. One can hardly overestimate the importance, if not the necessity of having the right lighting, atmospheric, and sky conditions. Many subjects which are flat and valueless under the hard sun of midday, the long shadows or early morning and late evening. The effect of clouds is not on the sky alone; their influence on the landscape itself is almost as great, in that casting of shadows on the far valleys an mountain ranges, separating them one from another, softening the blinding light, and imparting a mysterious beauty to the ethereal distances.”

To provide even more entrancing images in color, Willard mastered the combined artistry of photography with painting in Rembrandt oils over enlarged photographs. The combination of these mediums adds texture and hues that illuminate the scenes portrayed with realism and beauty in an eye-pleasing manner that is unique to Willard’s work.

Willard first began experimenting with painting over photographs in the late teens. Daughter Bettie said his first attempts resulted in photographs that merely looked tinted. Soon after, he developed the process of painting over a photographic image printed on tapestry paper. His work shows the reality of a photo combined with the texture and color of oil painting.

Bettie said “His ideas of color were the key to the result: the work of the painter or artist was to create the impression on the viewer’s eye that the artist wants to convey, not to try to represent nature exactly as its colors are. You cannot do this, as the closest thing to black is the mouth of a cave, but when you hold true black up to it is not black at all . . . It is the juxtaposition of colors that create the impression the artist wants.”

Hal Gould, a widely recognized authority on vintage photography, who for many years operated The Camera Obscura Gallery in Denver, Colorado, conducted a certified appraisal of the Willard Collection in 1998. His summary thoughts were as follows:

“Stephen H. Willard can be considered one of the four great western photographers of his time, along with Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Wynn Bullock. For over forty years, he operated a very successful fine art gallery at Palm Springs and at Mammoth Lakes, California. He established a prosperous market for his photographs and oil paintings, and at the same time, accumulating a vast and comprehensive collection of negatives of the Palm Springs area, the western desert, and the eastern Sierras, often photographing the same sites several times over the years to achieve the ultimate aesthetic and to record the extreme changes taking place in the environment as Palm Springs changed from sleepy hamlet to one of the world’s most popular resorts . . . “

In 1999, Dr. Beatrice Willard donated her father’s life’s work to the Palm Springs Desert Musem. This large gift of over 16,000 items includes original glass and film negatives, vintage photographs, hand-colored slides, photo paintings, postcards, stereographs, cameras, lenses and other photographic equipment, and personal papers and memorabelia, including maps, correspondence, and publications.

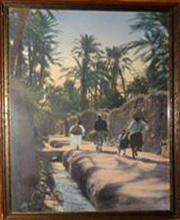

Willard’s World Travels and Art

Stephen Willard is mostly known for his photographs and paintings depicting scenes in the deserts and mountains of California. For many years he maintained studios in Palm Springs and Mammoth Lakes where he produced the majority of his work. However, his curiosity extended well beyond the confines surrounding those locations. In the 1920’s and 30’s when world travel was more arduous than it is today, it has been reported that by 1942 Stephen and his wife Beatrice had traveled over 300,000 miles in their journeys to foreign countries, often to remote locations not commonly visited at the time.

In addition to more common destinations in Europe, the Willards traveled to Asia, the Middle East, Africa and South America. Their journeys took them to such diverse places as Paris, Yokohama, the Himalayas and the Sahara. We know that they utilized a program offered by the Dollar Shipping Lines whereby they could disembark for a stay in one port and be picked up by another ship for transport to their next destination.

In a poem written by Stephen to his wife in 1936 he said:

It is with you, Brave Heart,

That my thoughts run back, across the years.

You, who gave up your own fond desires,

To labor with me, that we might go,

Together to the far places.

While not often seen, Willard took photographs and produced some paintings of scenes he encountered during his world travel. Although he focused his efforts at home toward landscape subjects, his work in foreign countries included urban scenes depicting the culture and people from the area. Here is a example from Algeria entitled “Through the Sunlit Lanes of Old Biskra.”

The Willard’s travel included forays down deep into Mexico when roads were primitive. amenities were scarce, and safety could be a concern. Daughter Bettie described one of their adventuresome trips into Mexico:

“On trips to Mexico . . . a man would go with them–Ignacio . . . a deputy sheriff. One time they got dysentery and could only drink beer. Mother always sat behind in the Pierce Arrow. They were on their way to Guaymas and had left the last town far behind. All of a sudden Mother says ‘stop the car Steve . . . there’s a dead man out there.’ They went back to town and reported it [and] went on their way.”

During one of their trips into Mexico they visited the town of Taxco, 100 miles southwest of Mexico City. This painting depicts a picturesque byway from Taxco typical of that era.

The paintings shown here are uncharacteristic of the Willard’s usual landscape efforts, but demonstrate the range of his skills when he chose to represent what he experienced during his travels to other lands.